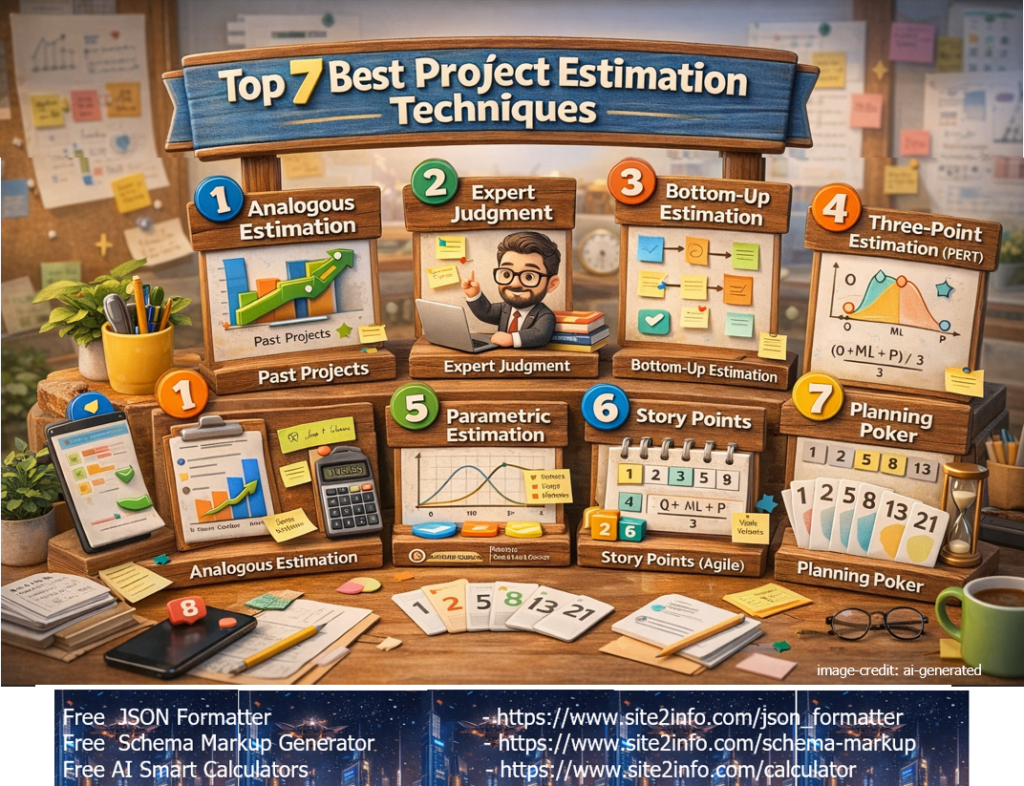

Detailed list of 7 Best Project Estimation Techniques

1️⃣ Expert Judgment

What it is:

Estimation based on the experience of senior team members or subject-matter experts.

Best for:

- New or complex projects

- Early-stage estimation

Pros: Fast, experience-driven

Cons: Can be biased

2️⃣ Analogous Estimation

What it is:

Estimating based on similar past projects.

Best for:

- Early planning

- High-level budgeting

Pros: Quick and simple

Cons: Less accurate if projects differ

3️⃣ Parametric Estimation

What it is:

Uses statistical formulas (e.g., cost per feature, hours per module).

Example:

10 pages × 8 hours/page = 80 hours

Best for:

- Repetitive or standardized work

Pros: Data-driven

Cons: Needs reliable historical data

4️⃣ Bottom-Up Estimation (Most Accurate)

What it is:

Estimate each task individually and sum them.

Best for:

- Detailed project plans

- Execution phase

Pros: Highly accurate

Cons: Time-consuming

5️⃣ Three-Point Estimation (PERT)

What it is:

Uses 3 values:

- Optimistic (O)

- Most Likely (M)

- Pessimistic (P)

Formula:(O + 4M + P) / 6

Best for:

- Risk-heavy projects

Pros: Accounts for uncertainty

Cons: Slightly complex

6️⃣ Agile Estimation (Story Points / Planning Poker)

What it is:

Estimation using relative sizing instead of hours.

Best for:

- Agile / Scrum teams

Pros: Team-based, flexible

Cons: Not ideal for fixed-scope contracts

7️⃣ Function Point / Use Case Estimation

What it is:

Estimation based on functional complexity rather than time.

Best for:

- Large enterprise software

- Regulated industries

Pros: Technology-independent

Cons: Requires expertise

🏆 Which Estimation Technique Is Best?

There is no single best technique.

Best practice: combine multiple methods.

⭐ Most commonly used combo:

- Early stage: Analogous + Expert Judgment

- Planning stage: Bottom-Up + Three-Point

- Agile projects: Story Points + Velocity

✅ Real-World IT Examples

🔹 1️⃣ Analogous Estimation – Website Development

Scenario:

Client asks: “How long will a 20-page corporate website take?”

Approach:

Last similar website took 6 weeks → estimate 5–7 weeks.

Why it works:

- Early proposal stage

- No detailed requirements yet

✅ Used for: Pre-sales, ballpark budgeting

❌ Not used for: Final contracts

🔹 2️⃣ Bottom-Up Estimation – E-Commerce Platform

Scenario:

Building an eCommerce site (Adobe Commerce / Shopify Plus)

Approach:

Break into tasks:

- UI Design → 40 hrs

- Backend APIs → 120 hrs

- Checkout → 60 hrs

- Payment Gateway → 30 hrs

- QA → 50 hrs

Total = 300 hrs

Why it works:

- Highly accurate

- Clear task ownership

✅ Best for: Fixed-scope projects, delivery planning

❌ Risk: Time-consuming to prepare

🔹 3️⃣ Three-Point Estimation – Payment Gateway Integration

Scenario:

Integration with external payment provider (high uncertainty)

| Estimate Type | Time |

|---|---|

| Optimistic (O) | 5 days |

| Most Likely (M) | 8 days |

| Pessimistic (P) | 14 days |

PERT Formula:

(5 + 4×8 + 14) ÷ 6 = 8.5 days

Why it works:

- Accounts for risk & unknowns

- Better stakeholder confidence

✅ Best for: Integration, migration, legacy systems

🔹 4️⃣ Agile Delivery Estimation – Mobile App Development

Scenario:

Scrum team delivering features in sprints

Approach:

- User Story A → 5 points

- User Story B → 8 points

- User Story C → 3 points

Team Velocity: 20 points / sprint

→ Delivery in 1 sprint

Why it works:

- Flexible

- Team-driven

- Continuous improvement

✅ Best for: Evolving requirements, product development

❌ Not ideal: Fixed-price contracts